The Real Threat to Your Startup

The hardest part of building is not building.

Most founders think their problem is building. It's not. The problem is deciding what not to build.

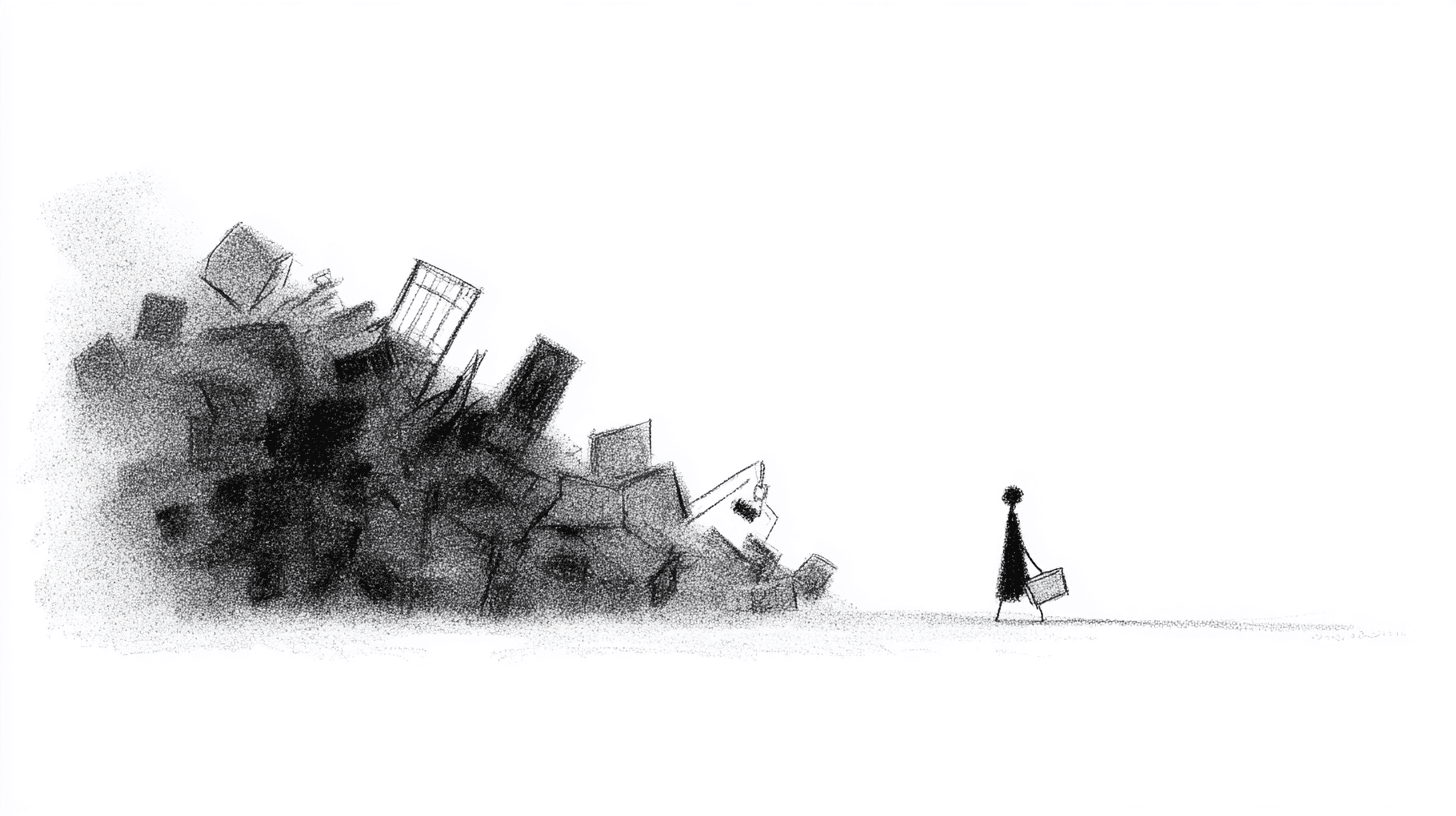

The startups that struggle aren't the ones who can't code. They're the ones who can't stop coding. They keep adding features the way some people keep adding adjectives, compulsively, defensively, as if more might somehow equal better.

The dangerous thing about feature creep is that it feels like progress. You're shipping code. Things are happening. But you're actually moving sideways while convincing yourself you're moving forward. Every feature you add before launch is a feature you're guessing users want. And most of those guesses will be wrong, not because founders are stupid, but because guessing what users want without users is like trying to hit a target blindfolded. You might get lucky. You probably won't.

Here's something most founders don't understand early enough: features aren't free even after you build them. They cost you once to build, again to test, and then forever to maintain. That button you added at 2 AM because it seemed clever? You're going to be debugging its interactions with other features for years. Technical debt is just another name for the accumulating weight of decisions you made before you understood the problem.

The best founders I've watched have a trick. They don't say no to ideas, they say “not yet.” They keep a list of everything they want to build, and then they ruthlessly ignore it until after launch. The list isn't a plan. It's a release valve for the part of your brain that keeps generating ideas when it should be shipping.

The real test for whether a feature belongs in v1 is simple: would the first ten users refuse to use your product without it? Not your target market, your actual first users. The ones you could call by name. If you're not sure who those people are, you have a bigger problem than scope creep.

Try cutting your MVP in half, then cutting it in half again. It sounds extreme. But the companies that succeed often launch with something so minimal it embarrasses them. Dropbox launched with a video demo and a waitlist, no working product at all. The Collison brothers tested Stripe by offering to integrate it for startups on the spot, before the product was ready for self-service. They weren't building the complete solution. They were learning whether the problem was real.

There's a version of this that's even more extreme: instead of building the smallest thing that works, build nothing at all. Test whether people want your product with a landing page. Run some ads. See if anyone cares. You can learn more from $100 in ads than from three months of coding.

But here's where I'm less certain. This advice assumes your market tolerates roughness, that early adopters will forgive missing features if the core works. That's true for most software. It's less true when trust is table stakes. If you're building something that handles money, or health data, or security, “move fast and break things” can break trust in ways you can't repair. Stripe could test with startups who'd tolerate bugs. A startup selling to banks probably can't.

There's also a failure mode on the other side. Some founders launch so early, with something so minimal, that they never learn whether the idea could work, only that the rough version didn't. If your MVP is a landing page and nobody signs up, you've learned something. But you haven't learned whether a real product would have worked. The signal is noisy.

So the advice isn't “always launch smaller.” It's “launch as small as you can while still learning something real.” The minimum viable product is the minimum that's still viable as a test.

The temptation to build more comes from fear. Fear that your product isn't impressive enough, that competitors will beat you, that users won't take you seriously. But in most markets, early adopters don't expect polish. They expect something that solves their problem. If your product does that, they'll forgive almost anything else. And if it doesn't, no amount of additional features will save you.

The best thing about launching early is that it ends the debate. You stop arguing about what users might want and start learning what they actually want. That conversation doesn't begin until you ship.

But it's worth being honest: launching is also when you discover whether you built the right minimum. Sometimes you learn you cut too deep. The skill isn't just cutting, it's knowing where to stop.