Agency

Jeff Bezos's regret minimization framework sounds wise until you think about it for five minutes.

The idea, which Bezos has described in interviews, is simple: when he was deciding whether to leave his hedge fund job to start Amazon, he imagined himself at 80 years old and asked which choice he'd regret more. Would he regret leaving a comfortable job to try this internet thing? Or would he regret never trying at all? The answer felt obvious, so he left. The framework has since become gospel in startup culture: when facing a big decision, project yourself to the end of your life and ask what you'd wish you'd done. Then do that.

The problem is you're asking the wrong person.

The 30-year-old trying to decide whether to leave their job and start a company is not the same person who will exist at 50, let alone 80. They have different values, different fears, different definitions of what constitutes a life well-lived. You're essentially asking a stranger to make your decisions for you. Worse, you're asking an imaginary stranger, a projection of a future self constructed entirely from your current assumptions about what matters.

I've watched my own priorities shift every decade in ways I couldn't have predicted. What seemed like the most important thing at 25 now looks like a strange obsession. What I dismissed as boring turned out to be the stuff life is actually made of. If my 25-year-old self had tried to minimize regret for my 45-year-old self, he would have optimized for completely the wrong things, because he didn't know what my 45-year-old self would care about. He couldn't. You can't know what a decade of living does to your values until you've lived it.

Now, you might object: there's still continuity. You remember being 25. You carry forward your memories, your relationships, your name. Philosophers have argued about this for centuries, whether the self persists through time or is rebuilt moment to moment. I don't need to settle that debate. What I'm claiming is narrower and harder to dispute: your preferences change in ways you can't predict. And regret minimization requires you to predict them. That's the problem. Even if you are, in some metaphysical sense, the same person at 80, you won't want the same things. The framework asks you to optimize for a target that moves in ways you can't see.

So regret minimization has a fatal flaw: it assumes a stability of preferences that doesn't exist. You're not one consistent set of values moving through time. You're a series of value systems, each inheriting the circumstances left by the previous one.

What should you do instead?

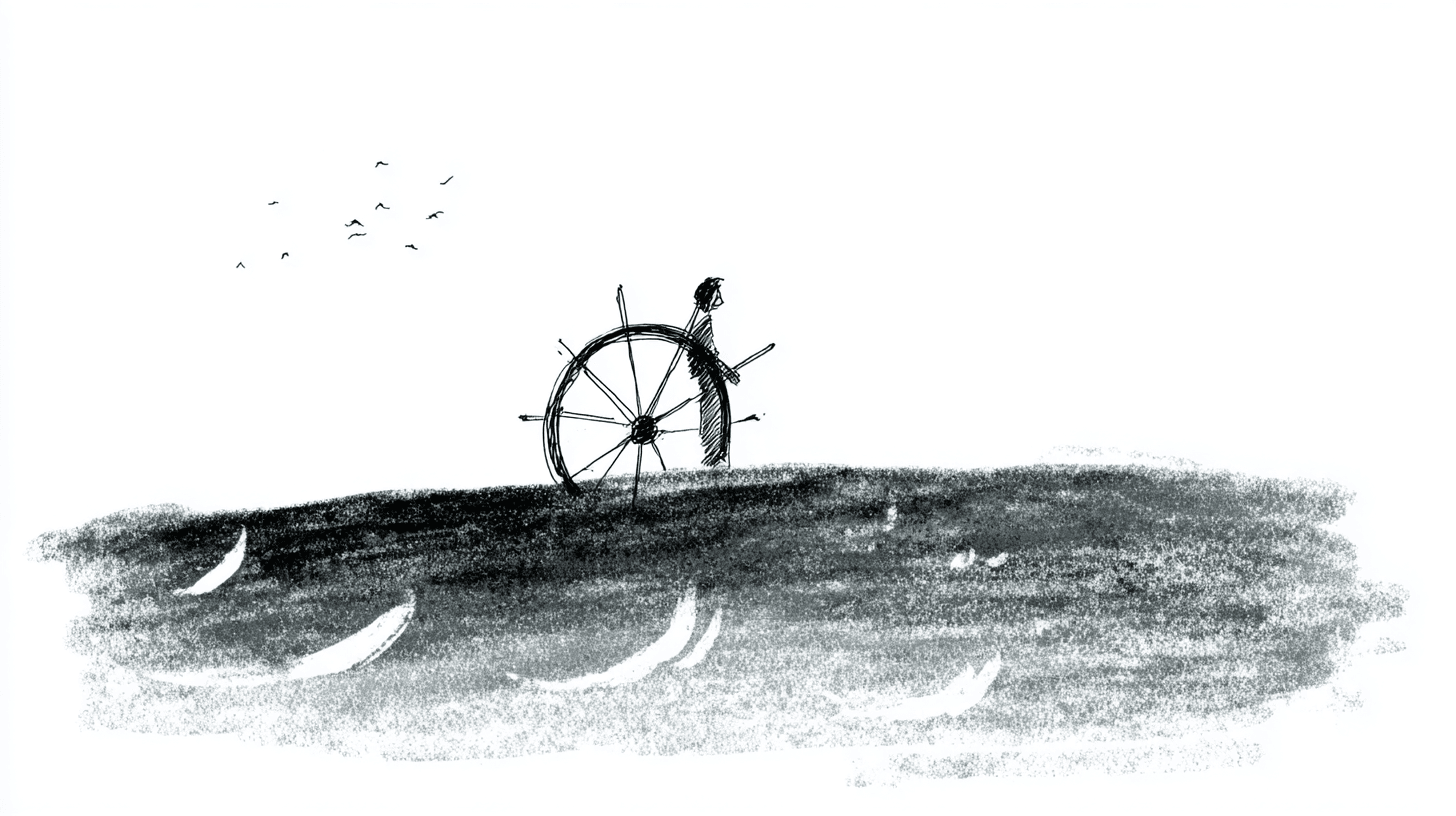

Steer, don't plan. The way to navigate a life is not to pick a destination in the distant future and walk toward it, but to make the best choice you can see right now, then correct course as new information arrives. This is how every other complex, unpredictable system gets navigated. Startups don't succeed by picking a business plan at the start and following it for ten years. They succeed by launching something, seeing what happens, and iterating fast.

The same is true for lives. The people I know who've ended up in good places didn't get there by executing a plan. They got there by being aggressive about trying things and aggressive about fixing mistakes. They treated their lives more like a dialogue than a monologue, they made a move, the world responded, they adjusted.

Consider the person deciding whether to leave their job for a startup. Regret minimization says: imagine yourself at 80, figure out which choice you'd regret less, commit. But that's a one-shot bet on a prediction you can't make. Steering says something different: take the option that gives you more information and more future options. If you can negotiate a leave of absence instead of quitting outright, do that. If you can test your idea nights and weekends first, do that. If you do leave and the startup fails, treat that as data, not disaster. The goal isn't to get the decision right the first time. It's to put yourself in a position to correct course fast when you inevitably get it wrong.

The key is the speed of adjustment. If you're going to make mistakes anyway, and you are, the variable you can control is how quickly you detect and correct them. Call it fast course correction. It's less romantic than imagining your 80-year-old self gazing back across a life without regrets. But it's more honest about how lives actually work.

There's a deeper problem with regret minimization, though, beyond its bad predictions. It's a defensive posture. You're trying not to lose. You're optimizing for the absence of a negative feeling. But the opposite of regret isn't satisfaction, it's engagement. The goal isn't to die with a clean scorecard. It's to be in contact with your life while you're living it.

A life spent trying to avoid regret is still a life spent in reaction to an imagined future judgment rather than in contact with the present. You're not making choices; you're hedging against a feeling you might have decades from now. That's a strange way to spend the only time you actually have.

Here's something hard to argue with: you feel like you have agency. Whatever your philosophical beliefs about free will, at the level of lived experience, you feel like you can choose. Decisions feel like decisions. When you pick up a glass of water, it feels like you're doing it.

If you have this feeling of agency, and you do, what's the point of not using it? Not deciding is also a decision. Outsourcing your choices to what other people tell you, or to an imaginary future self, is also a decision. But it's a decision to give away the one thing you actually have.

So use it. Make choices with the information you have now. When they turn out to be wrong, make new ones. Don't wait for certainty; it's not coming. Don't defer to your imagined 80-year-old self; you don't know who they are. You're here, now, with options in front of you that will never appear in exactly this form again.

Wouldn't it be a waste to reach the end of your life and realize you never really tasted it? Not because you chose wrong, but because you spent the whole time calculating instead of choosing, optimizing for a future feeling instead of living the present one. The strawberries were always there. You just never reached for them.